It's been a bit quiet over here beyond the Friday Fodder and that's because I promised myself I wouldn't post anymore until I actually tried to formulate what it is we're trying to do here. Let’s go!

Mission

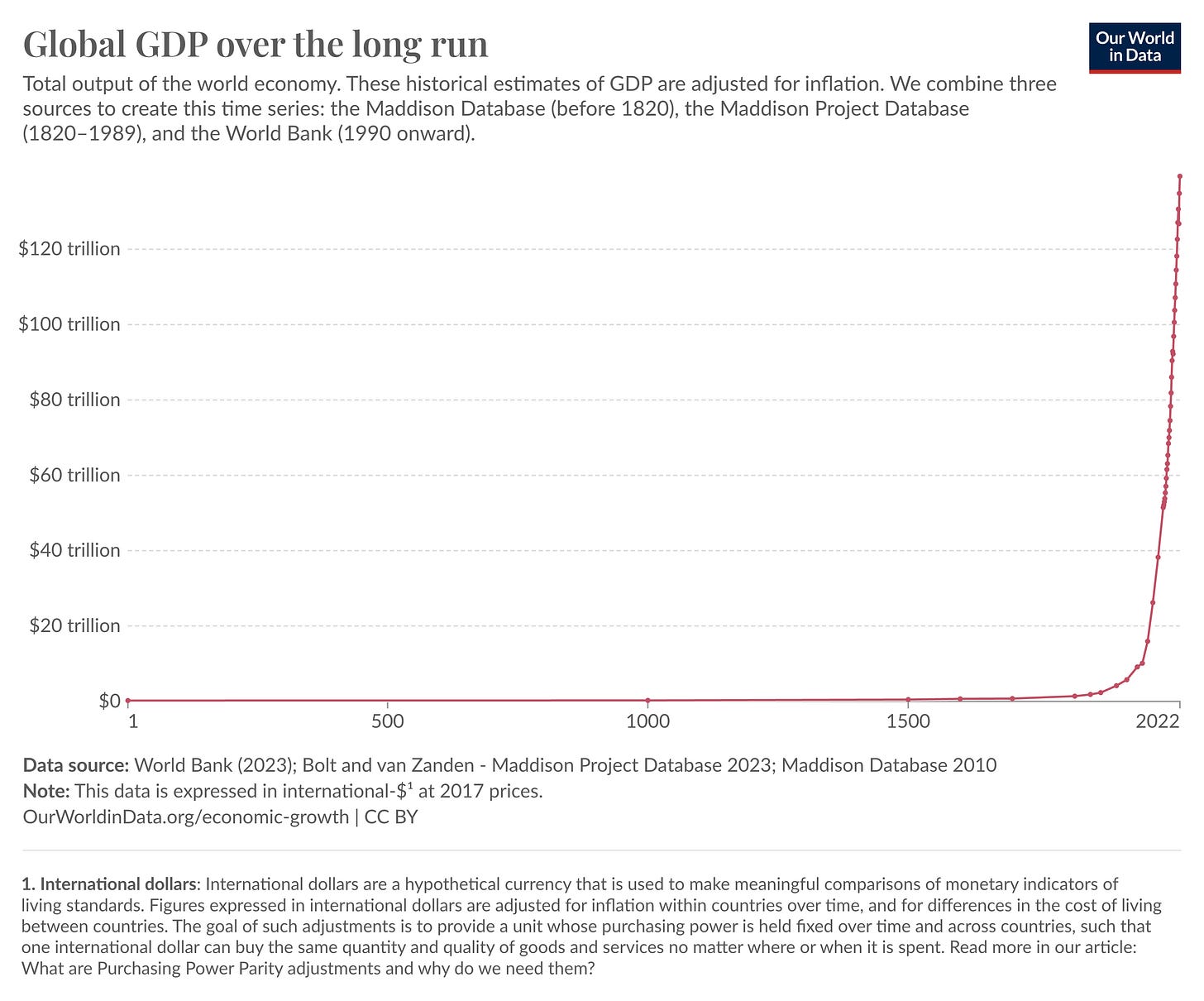

Take a look at this graph. The acceleration of technology is the fundamental attribute of humanity in the 21st century. This isn't a surprising new revelation. It's not something we think about regularly in our lives. But when you zoom out and look at a graph like GDP over time, you begin to realize the extent of this compounding.

Something happened about 300 years ago and the whole world started shifting. Science kicked off, individual freedoms became norms, capitalism and industrialization started cranking and we haven't looked back since.

I started a Substack for a couple reasons, because: 1) hitting the "Publish" button forces me to foster a compounding habit of writing and, more importantly, 2) I've had some things to say about an odd combination of modern topics that's hard to articulate. It involves tech, obviously, and people too, but that's not quite enough.

So, after a few months of quietly writing here, let's finally answer the question:

What are we doing here?

Since all this human progress accelerated a few hundred years ago, there's been a dichotomy of perspective. There's the full adoption folks, the all-in crowd, the ones that go nonstop, full blast, trying to move the needle as far and as fast as they can. The latest fad verb for these types is "accelerate" from the e/acc bros. Progress itself is a virtue, they say, and more progress at all costs is more virtuous and will end in a techno-utopia.

On the other side there's the anti movement, the minimalists, the Luddites — still named after the followers of King Ludd who rejected and burned the weaving machines of 19th century England.

And then there's most of us who don't think about this every day, we just ride the wave. There's a new iPhone out. An electric car will save me money. If I put this in Google Sheets I can share it easier than in Excel. We make normal, everyday decisions and whatever tech there is presents itself as our options.

The Veneer

There's a veneer that sits like a thick layer between our practical lives and all the underlying philosophies. Most of the time and for most of history the thickness of this veneer doesn't really matter. A wireless home phone in the 90s was more convenient than the corded variety but it didn't fundamentally change our relationship with time and physical space. Today smartphones are literally rewiring our brains. The faster technology goes, the more important the philosophy becomes.

So the first goal is to start scratching away at this veneer — to uncover the philosophy and frameworks of thought and virtue that underpin our world. People are clamoring for this. The way our world is changing is making everyone desperate for meaning and foundation. This is part of the reason why so many "new" philosophies and ideas have been entering everywhere from our church to our politics. Critical theories, megachurches, secular humanism, e/acc, woke, and the retreat to trad-lifestyles — all of these are modern searches to find meaning in the metaphysical destitution we experience amidst change.

The tradition of Western thought sits like an ancient redwood amongst all of these rootless modern ideologies, sometimes barely visible because its foundation has let it grow high and proud over so many millennia. It is remarkable how this tradition has anticipated our modern challenges. Socrates, for instance, had concerns about how the technology of written text would change the importance of memory and conversation, mimicking our own worries about smartphones and attention spans.

It shouldn't be a shock that tech heroes like Peter Thiel and Marc Andreesen are extraordinarily well read in the humanities and philosophy. Alex Karp of Palantir leans on Heidegger. Patrick Collison of Stripe has a deep bookshelf filled with philosophy of science and economic history. These aren't mere affectations — they represent a deep understanding that technological progress must be grounded in wisdom.

Starting from Socrates onward there exists a robust tradition of truth and virtue. From this trunk sprout the branches of empiricism and the scientific method, the university system through medieval monasteries, and even the very concept of progress through Christian theology's linear view of time. Where new and modern ideas often ignore all of this history or chase their own tails in endless deconstruction, the Western tradition provides tested tools for building up: natural law, virtue ethics, and the integration of faith and reason demonstrated by thinkers from Augustine to Aquinas.

To be more specific, I have found the Catholic perspective on the humanities to be the most insightful, whether it’s the ancient reasoning of Aquinas, the modern understanding of mimetic theory from René Girard, the pragmatic belief of CS Lewis, or even the Southern Gothic storytelling of Flannery O'Connor. Over and over, the best answers to the problems of our modern world I've found here. These thinkers share a remarkable ability to hold complexity — to embrace apparent contradictions rather than trying to resolve them into overdetermined either/or positions.

Both/And

GK Chesterton is the master of paradox. Where others seek to smooth away the tensions in modern life, Chesterton seems to delight in them. He sees the ability to maintain opposing truths as one of the keys to understanding reality:

“Christianity got over the difficulty of combining furious opposites, by keeping them both, and keeping them both furious.” — GK Chesterton

This both/and approach — a sort of paradoxical combinatorics — is the best way to think about the world. Here's what I mean:

Most of us don't embrace tech completely and we also don't try to eliminate it completely either. Instead of throwing our phone in the trash, we try to limit our screen time, or delete apps, or whatever. We end up trying to hybridize the accelerate and Luddite approaches. But this hybridizing leads to compromise and never really works. 2 hours of screen time per day isn't better than 4, not really. It's the same mindset, sitting in the messy middle with no real foundation to think about our choices.

Instead we need to hold a duality on our minds. We need to be all-in and all-out with technology. At the same time.

I often think of this as a barbell approach. There are places and ways where we need to adopt progress and technology and use it fully. There are other places where we should reject it completely.

So which are which? This is a simple question, but the implementation is profoundly hard and gets trickier with every new tech revolution. Should we automate away our everyday tasks of living like laundry? How should we allow AI to make medical diagnoses? Where does a prayer app like Hallow fit in? Are artificial wombs in our future? If Claude can write better than me, why should I bother? None of these questions are simple. They demand wisdom and virtue and flexibility, which is why the underlying philosophies to make these decisions are so important. We need our millennia of thought as a foundation.

And that's the second reason we're here, to explore what it means to sort this out. It will require diving into different topics about the state of technology and how it's changing and what's coming next. And sometimes we'll talk about the sociological, philosophical, and theological underpinnings. If we do these things, we can turn these questions into a path — a both/and path — that makes sense to our humanity and holds true to the Western tradition and the Catholic faith.

Why "Brains Are Plastic"

The barbell approach demands adaptability, plasticity, from us. We must be capable of switching between intense technological engagement and complete technological detachment, sometimes in the same day. Done well, this isn't compromise; it's mastery.

Even the Luddites, though usually scorned, were initiating a search for a kind of mastery. They made an effort to look at a new component of progress and evaluate the first-order changes this progress would cause. They saw (only) negative consequences and reacted to them.

We see our negative consequences today and react in the same ways. A small but growing segment of the population is walking back common technology. The most obvious examples are those with dumb phones and no social media, but that's only one component. The hyper-regulation that makes SpaceX test sonic booms on seals and the SEC serve Wells Notices to crypto companies exists in the same vein of thought, though often vastly different in impact. We see the progress in front of us and we are — justifiably or unjustifiably — scared.

Yet look at that GDP graph again. Measured over the long term, technology brings wonders. We can expect more wonders in the future, and faster too. Tim Urban has by far the most amusing way to measure this, which he calls Die Progress Units: how far someone has to be transported into the future that they would die from the level of shock. A farmer in 1000 AD would have lived in largely the same world in 1500, but would have a hard time with 1800. And someone living in 1800 would barely recognize 1950. And someone from 1950.. would they understand the 2020s? Maybe physically, but certainly not virtually. And will we be able to handle the 2030s? Nobody knows! It could be a radically different world.

So what do we do with this?

All of this involves an awful lot of brains. Not just mine and yours but also all the people around us and thinkers from the last thousand years. One of the most important underpinnings that we need to think about is how remarkably adaptable and changeable humans are. We're capable of the sorts of behavioral change that defies any other species. Our brains are literally plastic. Whether through biochemical wonders, evolutionary iteration, or the literal breath of God, we can change our mindsets, our addictions, our bad models. We can update our data and understand the world better than we could yesterday.

In short, we are capable of redemption. Brains Are Plastic serves as a fun way to remind us that we are as changeable as the technology around us, yet ultimately the change we are called to is redemptive. Because we are still the same plasticky, changeable humans driven forward by something ineffable, striving for virtue and meaning, searching for ourselves and for the face of God everywhere around us.

Two millennia ago, God gave us the ultimate both/and to ponder: the fully human and fully divine. And we are still trying to change, trying to grasp and understand that incredible gift. It remains the best expression of our humanity and our relationship with this world and its maker. Our ingenuity and genius, which comes from God, and our capability to progress and build new technology is a part of our humanity and our relationship with the divine.

Technology may be the biggest change in the 21st century. But the biggest secret of the 21st century is incarnation.

“Keep a little fire burning; however small, however hidden.” — Cormac McCarthy

A Note On Format

A book I keep coming back to (and am reading right now) is the Meditations by Marcus Aurelius. While the content is incredible ("be like a rocky promontory— "!), what makes it even more incredible is that this was his own private journal. Marcus Aurelius was not writing for an audience, he was writing to himself.

I find the easiest things to write are directly to my close friends in dialogue — because a big part of this is simply me working it out for myself. So even though this venue is public per se, I plan to (try to) preserve that spirit of intimate conversation. It will sometimes be irreverent. I like cursing; I think it gets the point across! It will also sometimes be wrong, and happily so.

The thing I find most important about the Meditations is that it is honest. When you are writing for yourself, there is no hiding. Paul wrote to the Ephesians to "be renewed in the spirit of your mind" (4:23). Same journey, different paths.

Onward!